California’s grid reliability struggles have intensified in recent years as extremes summer heat strains the system and threatens power outages. The state’s grid reliability is also inextricably linked to issues of improving energy affordability and achieving California’s ambitious clean energy goals. With California’s power woes apparent, Western grid regionalization has been raised as a potential path to address these related concerns.

What is Western grid regionalization?

Western grid regionalization is the idea of better connecting and coordinating power grids throughout the West. It’s not a new concept. It gained traction in California in 2018, although that particular effort fell short. But once again, the debate is becoming topical as another push for grid regionalization gains momentum.

Like onions and ogres, there are layers to the US power grid. And to understand Western grid regionalization, its likely impacts, and the arguments for and against it, it would be best to first understand the layers.

Let’s start with the interconnections

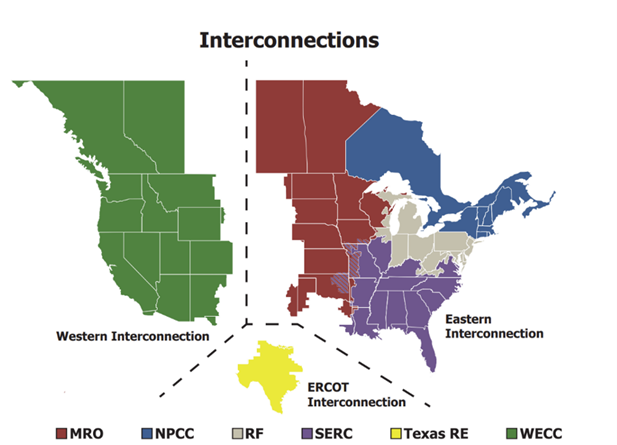

At the highest level, the contiguous United States is composed of three electrical grids: the Western Interconnection, the Eastern Interconnection, and the Texas Interconnection. (The Western and Eastern Interconnections reach beyond US borders into parts of Mexico and Canada.) Technically, these interconnections are linked to each other, but the transmission capacity among them—the ability to move electricity from one grid to another—is very limited, so the grids largely operate independently.

At the next level, there are the regional entities responsible for enforcing reliability standards. There’s a lot that goes into the development of these standards, but ultimately this is a layer to help ensure regional power systems are reliable.

While regional entities enforce reliability standards for the grid, the grid itself is managed by a layer of smaller entities called balancing authorities. Balancing authorities operate their area’s power transmission, making sure that electricity supply and demand are equal at all times of the day. This occurs in real time and is a necessary function for the grid to operate smoothly so our lights stay on.

There are two main types of balancing authorities: regional transmission organizations (RTOs) and individual utilities. There also are independent system operators (ISOs), but for our purposes, RTOs and ISOs can be used interchangeably, so we’ll stick with the RTO terminology. RTOs are generally multistate entities that function as balancing authorities with additional responsibilities, such as operating the wholesale energy markets in their area and overseeing transmission planning. In areas that are not part of an RTO, utilities take on the role of balancing authority.

Notably, the Western Interconnection only has one RTO—the California Independent System Operator (CAISO)—and the rest of the region is managed by individual utilities. This fragmented landscape can be an obstacle to quickly transition to clean energy and is in stark contrast to the situation in the Eastern Interconnection, which is largely managed by RTOs.

So, simply put, grid regionalization refers to consolidating many balancing authorities under a single grid operator, in this case, to become a Western RTO. Less simple are the impact that a regional grid would have on how California’s power system operates and plans for the future.

How would a regional grid in the West be different?

It’s worth explicitly stating that the grid regionalization talk in this blog is about expanding the CAISO footprint to more states in the West, as opposed to the Southwest Power Pool’s expansion into the West or the creation of an entirely new RTO. A larger Western RTO would create four main differences from how the grid currently operates.

Resource sharing could improve. Balancing authorities are required to plan for enough resources to ensure a reliable grid. This is known as resource adequacy and it’s a complicated process that plans for enough supply to meet unusually high levels of electricity demand to make sure the power stays on even during rare events. A regional grid would have a larger and more diverse pool of generation and load. These differences in peak load times and diversity of resource generation would allow for better resource coordination to support grid reliability. For example, California’s peak load is in the summer while the Pacific Northwest’s peak load is in the winter. Rather than procuring all the resources needed to meet their peaks, regions could share resources to support each other’s peak loads. Because of this efficiency, overall resource adequacy requirements could be lower than the sum of individual resource adequacy requirements. When all is said and done, lower resource adequacy requirements could theoretically reduce utilities’ reliance on fossil fuels and reduce the cost of resource adequacy requirements for ratepayers.

It would change Western energy markets. RTOs generally balance supply and demand more efficiently because they operate wholesale energy markets, both “day-ahead” and “real-time.” As the terms suggest, the day-ahead market transacts for the day prior to consumption, while the real-time market occurs close to the time of consumption. These energy markets signal to an RTO how much energy will be needed and allow RTOs to schedule and dispatch the least expensive, and often cleanest, generators first.

California has already taken steps toward these energy markets. In 2014, CAISO launched the Western Energy Imbalance Market (WEIM), a real-time energy market for the West that as of 2022 included 19 participants. The success of the WEIM has led to development of the Extended Day Ahead Market (EDAM), which is in the final stages of design. Assuming the EDAM established itself and draws broad participation, there likely wouldn’t be huge changes to California’s energy markets under a full Western RTO, since these energy markets would already be operating throughout the West. However, forming an RTO would guarantee these energy markets and the cost efficiencies associated with them.

Transmission planning could be vastly more efficient. When a balancing authority needs to import electricity from outside of its area, it must coordinate with other balancing authorities to expand transmission and allocate rights and costs. This can make it more difficult to access cheaper or cleaner energy. A Western RTO would have access to the entire transmission grid in its area, allowing it to efficiently accommodate growth in energy supplies.

Additionally, RTOs can better plan their future transmission infrastructure as demand and resource mixes evolve. This is especially useful when dealing with transmission across state lines that can often face political and financial obstacles. The impacts of a robust transmission system are numerous and critically important to reach a clean energy future.

Governance would expand beyond state borders. CAISO’s board is currently appointed by California’s governor and confirmed by the state Senate, meaning California’s interests are closely aligned to CAISO’s operations. A regional grid would need a new governance structure, otherwise there’s no chance that utilities outside of California would join. It’s important to note that CAISO’s current governance structure is written into California law and thus new legislation would be needed to change the current system. Whether that will happen is still up in the air, but it’s a must-happen first step for CAISO to expand into a larger Western regional grid. This is the step that tripped up the 2018 grid regionalization push.

In theory, a Western RTO would improve grid reliability, energy market efficiency, and regional transmission planning. These all have the potential to accelerate the transition to clean energy for Western states and lower energy costs for ratepayers. For example, California’s excess daytime solar could be exported to other states to displace more expensive, non-renewable generation. Lower resource adequacy requirements could accelerate the retirement of fossil fuel plants. Coordinated transmission planning could make it more financially viable to build and connect new renewable projects. There’s a long list of potential benefits, but how a regional grid actually plays out will depend on implementation.

While the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) believes a Western regional grid offers many potential benefits, some folks are concerned that grid regionalization could backfire and hamper California’s transition to clean energy. UCS plans to post a series of blogs to dig deeper into the debate and examine these concerns. But as California and other states work to clean their grids and reach their broader energy goals, grid regionalization could be an opportunity to accelerate that progress.