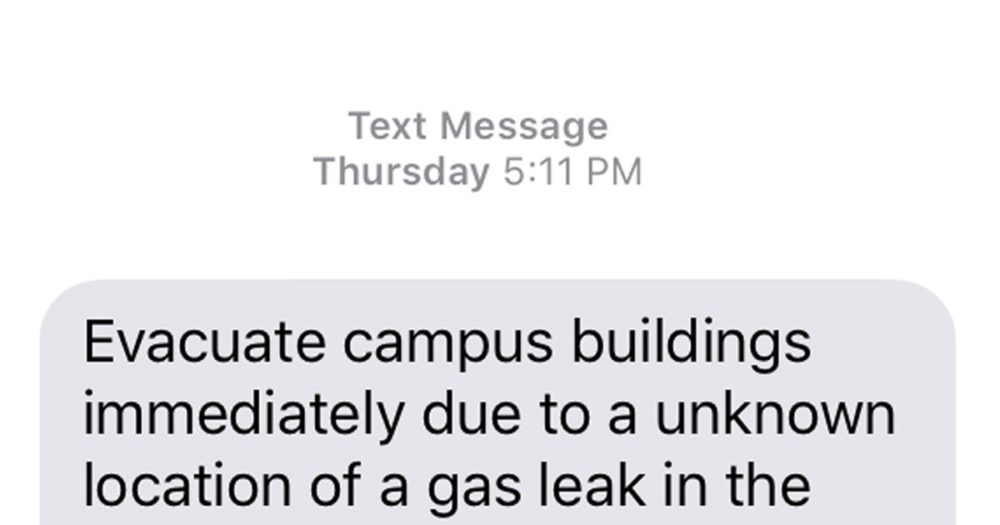

The calls and texts from my kids’ school started coming in at 5:11 p.m. last Thursday: “Evacuate campus buildings immediately.” Some of the messages included mention of a gas leak. The northern Massachusetts headlines about gas leaks, fires, and explosions were scary, and this was my own family potentially in harm’s way.

After events like that, it’s easy to imagine wanting to be done with fossil fuels. Not just because of their climate change, broader environmental, or public health impacts, but also because of the problems, even rare ones, that can arise from having those fuels right where we live.

But where might that fossil fuel reduction plan happen on the home front? Here are a few ideas.

Getting beyond fossils

Photo: Pixabay/Magnascan

Even with all the thinking I do about moving away from fossil fuels and toward clean energy, those messages from school brought an immediacy to the need for transition that I hadn’t felt before. When my family got past the emergency stage, I found that last week’s events were prompting me to rethink the role that fossil fuels play in my own life, knocking out of me the remnants of my that’s-the-way-it-is-because-that’s-the-way-it’s-always-been mindset.

The first part for addressing our home fossils is understanding where they are (in fuel form in this case—not, say, as plastic plates, polyester quick-dry clothing, or vinyl siding). The second part is understanding the options for dealing with them.

In my house, that first part comes down to space heating, water heating, cooking, and transportation. No small list. For the second part, though, the catalogue of options is definitely up to the challenge.

Here’s a look at the opportunities in each of those areas, and where my own journey stands.

Cutting fossil use in space heating

Our winters are cold, and in New England, space heating accounts for 60% of household energy use. While natural gas is the fuel for more than half, homes in these parts also use fuel oil in a big way; in Massachusetts, heating oil accounts for close to 30%.

Moving from oil to gas cuts down on carbon pollution, using high-efficiency gas furnaces and boilers takes it to the next level, and insulating homes better can cut down on any fuel. But none of those results in ditching on-site fossils altogether.

Fortunately, heat pumps do. The two options are ground-source/geothermal, which take advantage of the constant temperature underground, and air-source, which miraculously harvest heat from even really cold air (and have gotten good in recent years at handling frigid northern temperatures). And they both do it with electricity as the only input.

I haven’t gotten to that stage yet. After becoming a homeowner a while back, I upgraded my heating equipment to the highest-efficiency units I could find. But heat pumps weren’t really on my radar screen. So there’s room for progress there.

Cutting fossil use in water heating

The next big category for fossil use in our houses is water heating; it accounts for 16% of home energy use in Massachusetts. Efficiency is an opportunity here, too, but again, only a partial solution if it’s a natural gas- or oil-fired unit.

The options for fossil freedom lie in electricity and the sun. For our home, I put in a solar water heating system, with a backup to boost it as needed. That booster is gas-fired, but could have been electric.

Another option is electric with, again, heat pumps to the rescue. Like their space-heating brethren, heat-pump water heaters draw heat from their surroundings. In this case, that adds up to water getting heated two to three times as efficiently as it would with a conventional electric (resistance) water heater.

My solar heat as of Monday. No sense wasting all that sunshine.

Cutting fossil use in cooking

Most of the time these days, the choice for frying eggs or roasting potatoes is between gas and electricity. Gas devotees like its responsiveness (though electrics may often actually have the edge in performance).

When we updated our old kitchen a few years back, we switched from gas to electric, but not a standard one. Instead of a resistance (glowing coil) kind, we went with an induction cooktop—electric, efficient, and really responsive (and able to boil water in no time flat).

Cutting fossil use in transportation

Our transit of the house in search of fossil fuels shouldn’t ignore the garage, and gasoline. The obvious solution is electric vehicles, and it’s an option that’s so much more real than it was when I drove EVs back in the 1990s. Add in walking, biking, and electric buses, and you’re cruising without carbon (onsite).

My ride, when I’m not on my bike or a train, is efficient (a 2001 first-gen hybrid, still, at 196,000 miles, getting 45 miles to the gallon), but still gas-powered. My wife’s, though, is pure electric—not a gas gallon in sight.

Home fossil use beyond the home

There’s actually one more entry for this list: electricity. This might seem like an odd thing to discuss when we’re talking about fossil fuels in the home, but let’s face it: A lot of the approaches above involve switching to a plug, and we’re not necessarily interested in just exporting our fossil problem with the out-of-sight-out-of-mind approach.

Fortunately, there are options here, too. One is to make your own fossil-fuel power, particularly with solar electric (photovoltaic) panels. If you’ve got the wherewithal and the roof, for example, you can look into putting up a solar array (and maybe even adding batteries). Or you can see about joining in with neighbors in a community solar system.

A more broadly available fossil fix is to buy green power. If your utility gives you the option, you can choose a fossil-free mix in place of whatever default electric mix might otherwise supply you. Or you can buy an equivalent amount of renewable energy credits (RECs) to green up your power supply.

We went solar two years ago, and generate enough to cover all of our home electricity use and a portion of the car. For the rest of our usage, my utility had been offering a REC option, and I’d been a loyal customer till that program went away; I’ll be looking to find a successor option.

Continue the journey

Home sweet lower-fossil-fuel home (Photo: J. Rogers)

Not all of these opportunities are available to all of us (think renters, for example). Money, too, is a consideration, and not all the options above are cheap (though some can actually save you money). But times like these call for do-what-you-can and beyond-the-wallet thinking. (Including because of the expense of the investments that someone is going to have to make, in the case of these events, to improve safety even without nixing the fossil fuels.)

Last Thursday, many of us in my area were lucky. My boys and their schoolmates evacuated and waited it out in a field. We picked up our kids, and adopted for the night a couple of extra who were more affected by the gas fires. Our town is supplied by a different gas network from the gas-fire communities, and we have a different power company, so didn’t lose power when service got cut off in affected communities.

But fossil fuels are certainly a part of our lives as much as they were for those who got hit by last week’s events: We have natural gas in our home, gasoline in our garage, and neighbors who heat with oil. So the journey continues.

When it comes to fossil fuel use in our homes, we’ve got options, and plenty of reasons to exercise them. Fossil fuels’ days of fossil fuels are numbered. Accelerating that phase-out is in our hands… and looking better all the time.