Looking across the San Francisco Bay at the city’s rapidly rising skyscrapers, it’s easy to see why Ingrid Ballman and her husband chose to move to the town of Alameda from San Francisco after their son was born. With streets lined with single family bungalows painted in a rainbow of pastel colors and restaurant patios lined with senior citizens watching pelicans hunt offshore, Alameda is a world away from the gigabits per second pace of life across the bay.

Children playing along Alameda’s Crown Memorial State Beach along San Francisco Bay. An idyllic place to play, the California State Department of Parks and Recreation describes the beach as “a great achievement of landscaping and engineering,” a description that applies to much of the Bay Area’s waterfront.

“I had a little boy and it’s a very nice place to raise a child–very family-oriented, the schools are great. And we didn’t think much about any other location than Alameda,” Ballman says. Alameda has been, by Bay Area standards, relatively affordable, though with median home prices there more than doubling in the last 15 years, this is becoming less the case.

After Ballman and her husband bought their home she began to think more about the island’s future. “At some point,” she says carefully, “it really became clear that we had picked one of the worst locations” in the Bay Area.

A hotspot of environmental risk

The City of Alameda is located on two islands…sort of. Alameda Island, the larger of the two, is truly an island, but it only became so in 1902 when swamps along its southeastern tip were dredged and the Oakland Estuary was created. Bay Farm Island, the smaller of the two, used to be an island, but reclamation of the surrounding marshes has turned it into a peninsula that is connected to the mainland. In the 1950s, Americans flocked to suburbs in search of the American Dream of a house with a white picket fence and 2.5 children, and Alameda Island, home to a naval base and with little space for new housing, responded by filling in marshes, creating 350 additional acres. Bay Farm Island was also expanded with fill to extend the island farther out into the bay.

The filling of areas of San Francisco Bay was common until the late 1960s, when the Bay Conservation and Development Commission was founded.

Many Bay Area communities are built on what used to be marsh land. These low-lying areas are particularly susceptible to sea level rise and coastal flooding.

While many former wetland areas are slated for restoration, many others now house neighborhoods, businesses, and schools, and are among the Bay Area’s more affordable places to live. The median rent for an apartment in parts of San Mateo and Alameda Counties where fill has been extensive can be half what it is in San Francisco’s bedrock-rooted neighborhoods.

When Bay Area residents think about natural hazards, many of us think first of earthquakes. In Alameda, Ballman notes, the underlying geology makes the parts of the island that are built on fill highly susceptible to liquefaction during earthquakes. It is precisely this same geology that places communities built on former wetlands in the crosshairs of a growing environmental problem: chronic flooding due to sea level rise.

Chronic inundation in the Bay Area

Ballman studies a map I brought showing the extent of chronic inundation in Alameda with a moderate sea level rise scenario that projects about 4 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century. The map is a snapshot from UCS’s latest national-scale analysis of community-level exposure to sea level rise.

“Right here is my son’s school,” she says, pointing to a 12-acre parcel of land that’s almost completely inundated on my map. With this moderate scenario, the school buildings are safe and it’s mostly athletic fields that are frequently flooded.

I haven’t brought along a map of chronic inundation with a high sea level rise scenario–about 6.5 feet of sea level rise by 2100–for Ballman to react to, but with a faster rate of sea level rise, her son’s school buildings would flood, on average, every other week by the end of the century. While this scenario seems far off, it’s within the lifetime of Ingrid’s son. And problems may well start sooner.

Seas are rising more slowly on the West Coast than on much of the East and Gulf Coasts, which means that most California communities will have more time to plan their response to sea level rise than many communities along the Atlantic coast. Indeed, by 2060, when the East and Gulf Coasts have a combined 270 to 360 communities where 10% or more of the usable land is chronically inundated, the West Coast has only 2 or 3. Given how densely populated the Bay Area is, however, even small changes in the reach of the tides can affect many people.

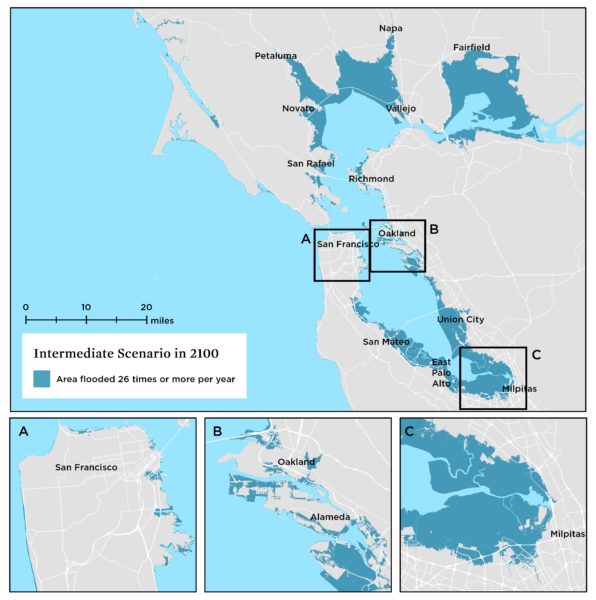

As early as 2035 with an intermediate sea level rise scenario, neighborhoods all around the Bay Area–on Bay Farm Island, Alameda, Redwood Shores, Sunnyvale, Alviso, Corte Madera, and Larkspur– would experience flooding 26 times per year or more—UCS’s threshold for chronic flooding–with a moderate scenario. By 2060, the number of affected neighborhoods grows to include Oakland, Milpitas, Palo Alto, East Palo Alto, and others along the corridor between San Francisco and Silicon Valley.

By 2100, the map of chronically inundated areas around the Bay nearly mirrors the map of the areas that were historically wetlands.

By 2100, with an intermediate sea level rise scenario, many Bay Area neighborhoods would experience flooding 26 times or more per year. Many of these chronically inundated areas were originally tidal wetlands.

Affordable housing in Alameda

Like many Bay Area communities, Alameda has struggled to keep up with the demand for housing–particularly housing that is affordable to low- and middle-income families–as the population of the region has grown. In the past 10-15 years, large stretches of the northwestern shore of the island have been developed with apartment and condo complexes.

Driving by the latest developments and glancing down at my map of future chronic inundation zones, I was struck by the overlap. With a high scenario, neighborhoods only 10-15 years old would be flooding regularly by 2060. The main thoroughfares surrounding some of the latest developments would flood by the end of the century.

While the addition of housing units in the Bay Area is needed to alleviate the region’s growing housing crisis, one has to wonder how long the homes being built today will be viable places to live. None of this is lost on Ballman who states, simply, “There are hundreds of people moving to places that are going to be underwater.”

Many of Alameda’s newly developed neighborhoods would face frequent flooding in the second half of the century with intermediate or high rates of sea level rise.

“Some of the more affordable places to live,” says Andy Gunther of the Bay Area Ecosystems Climate Consortium, “are the places that are most vulnerable to sea level rise, including Pinole, East Palo Alto, and West Oakland.” Many of these communities that are highly exposed to sea level rise are low-income communities of color that are already suffering from a lack of investment. These communities have fewer resources at their disposal to cope with issues like chronic flooding.

Bay Area action on sea level rise

How neighborhoods–from the most affordable to the most expensive–throughout the Bay Area fare in the face of rising seas will depend, in part, on local, state, and federal policies designed to address climate resilience. A good first step would be to halt development in places that are projected to be chronically inundated within our lifetimes.

For Bay Area and other Pacific Coast communities that will experience chronic inundation in the coming decades, there is a silver lining: For many, there is time to plan for a threat that is several decades away, compared to communities on the Atlantic Coast that have only 20 or 30 years. And California is known for its environmental leadership, which has led to what Gunther calls an “incredible patchwork” of sea level rise adaptation measures.

Here are some of the many pieces of this growing patchwork quilt of adaptation measures:

- Last year, with the signing of bill AB 2800, California Governor Jerry Brown established the Climate-Safe Infrastructure Working Group. This group aims to integrate a range of future climate scenarios into infrastructure design planning.

- The City of San Francisco has developed official guidance for incorporating sea level rise into capital planning projects.

- With funding from the EPA, the Novato Watershed Program is taking advantage of natural processes to reduce flood risk along Novato Creek.

- The San Francisco Estuary Institute is working to understand the natural history of San Francisquito Creek, near Palo Alto and East Palo Alto, in order to develop functional and sustainable flood control structures and restoration goals.

- The Santa Clara Valley Water District is scheduled to begin work this summer to improve the drainage of Sunnyvale’s flood-prone East and West channels and reduce flood risk for over 1,600 homes. The District is also addressing tidal flooding problems in cooperation with the US Army Corps of Engineers.

- As part of its extensive broader efforts to address sea level rise, San Mateo County installed virtual reality viewfinders along the shoreline aimed to engage the public in a discussion of how sea level rise would affect their community.

- On a regional level, the Bay Conservation Development Commission partnered with NOAA and other local, state, and federal agencies for the Adapting to Rising Tides project, which provides information, tools, and guidance for organizations aiming to address climate-related challenges.

- There is currently a Resilient by Design competition for the Bay Area that’s engaging engineers, community members, and and designers in developing innovating solutions to sea level rise.

In South San Francisco Bay, a number of shoreline protection projects have been proposed or are underway.

A regional response to sea level rise

Gunther notes that “We’re still struggling with what to do, but the state, cities, counties, and special districts are all engaged” on the issue of sea level rise. With hundreds of coastal communities nationwide facing chronic flooding that, in the coming decades, will necessitate transformative changes to the way we live along the coast, regional coordination, while challenging will be critical. Otherwise, communities with fewer resources to adapt to rising seas risk getting left behind.

“There’s a regional response to sea level rise that’s emerging,” says Gunther, and the recently passed ballot measure AA may be among the first indicators of that regional response.

In 2016, voters from the nine counties surrounding San Francisco Bay approved measure AA, which focuses on restoring the bay’s wetlands. Gunther says that this $500+ million effort could prove to be “one of the most visionary flood protection efforts of our time.” The passage of Measure AA was particularly notable in that it constituted a mandate from not one community or one county, but all nine counties in the Bay Area.

Toward a sustainable Bay Area

Waves of people have rushed in and out of the Bay Area for over 150 years, seeking fortunes here, then moving on as industries change. The stunning landscape leaves an indelible mark on all of us, just as we have left a mark on it, forever altering the shoreline and ecosystems of the bay.

For those of us, like Ingrid Ballman and like me, who have made our homes and are watching our children grow here, the reality that we cannot feasibly protect every home, every stretch of the bay’s vast coastline, is sobering. All around the bay, incredible efforts are underway to make Bay Area communities safer, more flood-resilient places to live. Harnessing that energy at the regional and state levels, and continuing to advocate for strong federal resilience-building frameworks has the potential to make the Bay Area a place we can continue to live for a long time, and a leader in the century of sea level rise adaptation that our nation is entering.